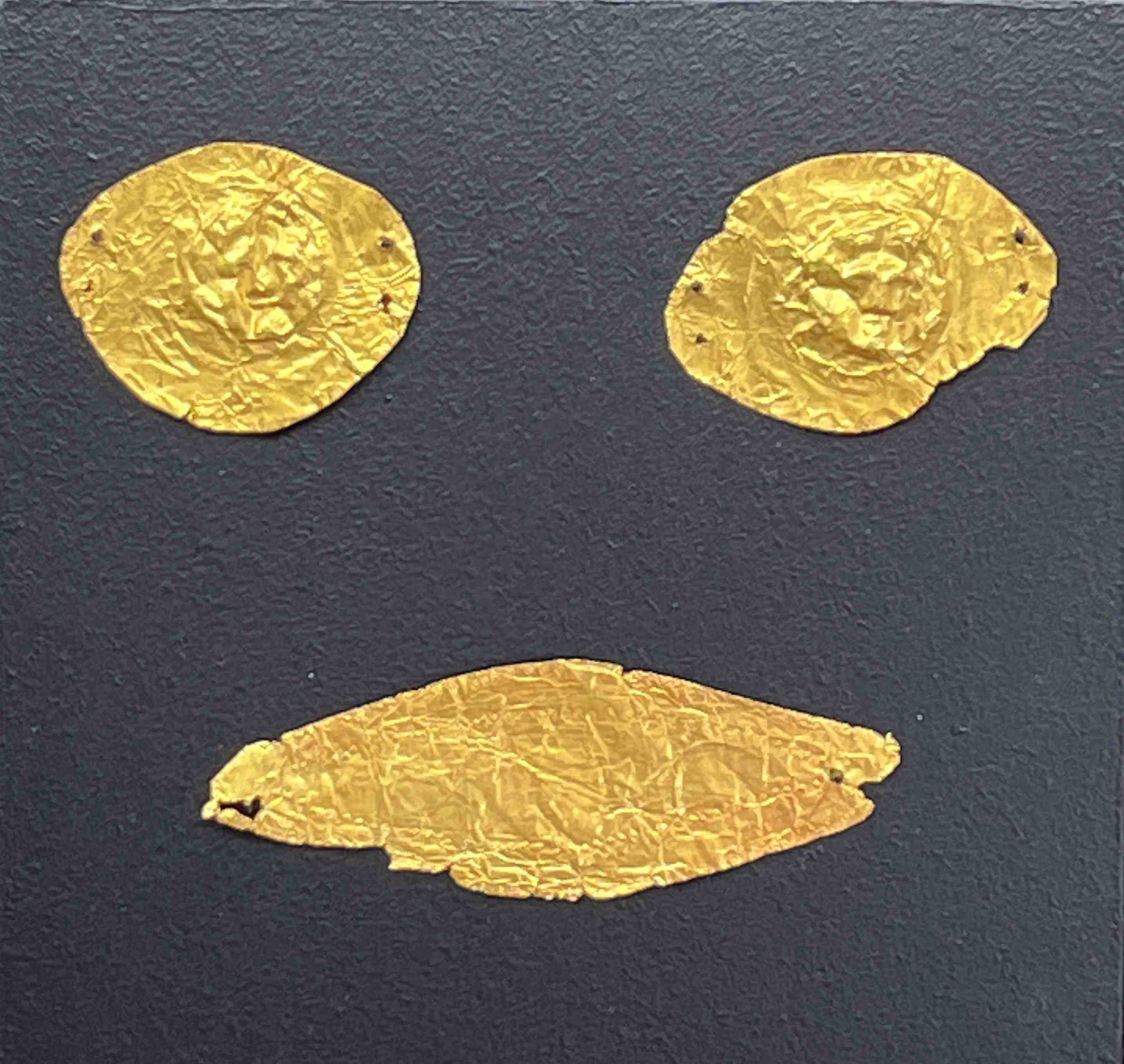

Ancient gold funerary mouthpieces

The oval ornaments of thin sheet gold of the type illustrated here have given rise to a number of theories as to their use. Talking about a Greek grave discovered in Olbia in 1891, E. H. Minns (in "Scythians and Greeks") describes a chamber lined with stone in which lay two skeletons, a man and a woman, with gold leaves upon eyes, mouth and ears. He goes on to suggest that, like funeral masks, they served to make it less painful to look upon the face of the dead at the time of the funeral ceremony and at the same time prevented the entrance of demons into the body through these openings. A number of mouthpieces have been found in place during excavations, and Maxwell-Hyslop ("Western Asiatic Jewellery, 3000-612 B.C.") recalls an example from Beth Shan (Syria) which was found inside an Iron Age anthropoid sarcophagus, 1200-1000 B.C. There use is equally attested in many cases by the embossed representations of lips which can be seen on some early specimens.

In "Greek and Roman Jewellery", R. A. Higgins discusses mouthpieces alongside diadems. The shape is common to both in many cases, although attribution of those with a straight lower edge to the diadem class is easily acceptable today. They share the piercings at the ends, through which a cord passed to hold them in place around the head. The mouthpieces also share with diadems the decoration typical of their period; strips were stamped with rosettes, palmettes, spirals, dots, and these patterns can help in dating. F. H. Marshall ists the items from the excavations at Enkomi, Cyprus, carried out by the Museum in 1896. The decoration was typical of the Cypriote "Mycenaean" period, 1300-1000 B.C. and this dating was further supported by the discovery of the Egyptian scarabs of the late 18th and 19th dynasties (curiously some objects from Enkomi were stylistically comparable with objects from Geometric tombs at Assarlik and excavations at Ephesus which suggested a date of 8th-6th cent. B.C.).

The Enkomi examples are perhaps the best known in this country but similar gold bands have been found at Rhodes, Hasanlu (Iran) and Meggido (Palestine) indicating a widespread use of the fashion. The examples listed here for the most part lack decoration to assist in dating. They are Hellenic rather than Cypriote, and more likely to date from the later period. Although the practice can be seen in 13th. cent. B.C., Seleucid graves in Mesopotamia provided evidence of the same practice, and the woman in the tomb at Olbia had a silver coin in her mouth, countermarked so as to date it to the 1st. cent. B.C.