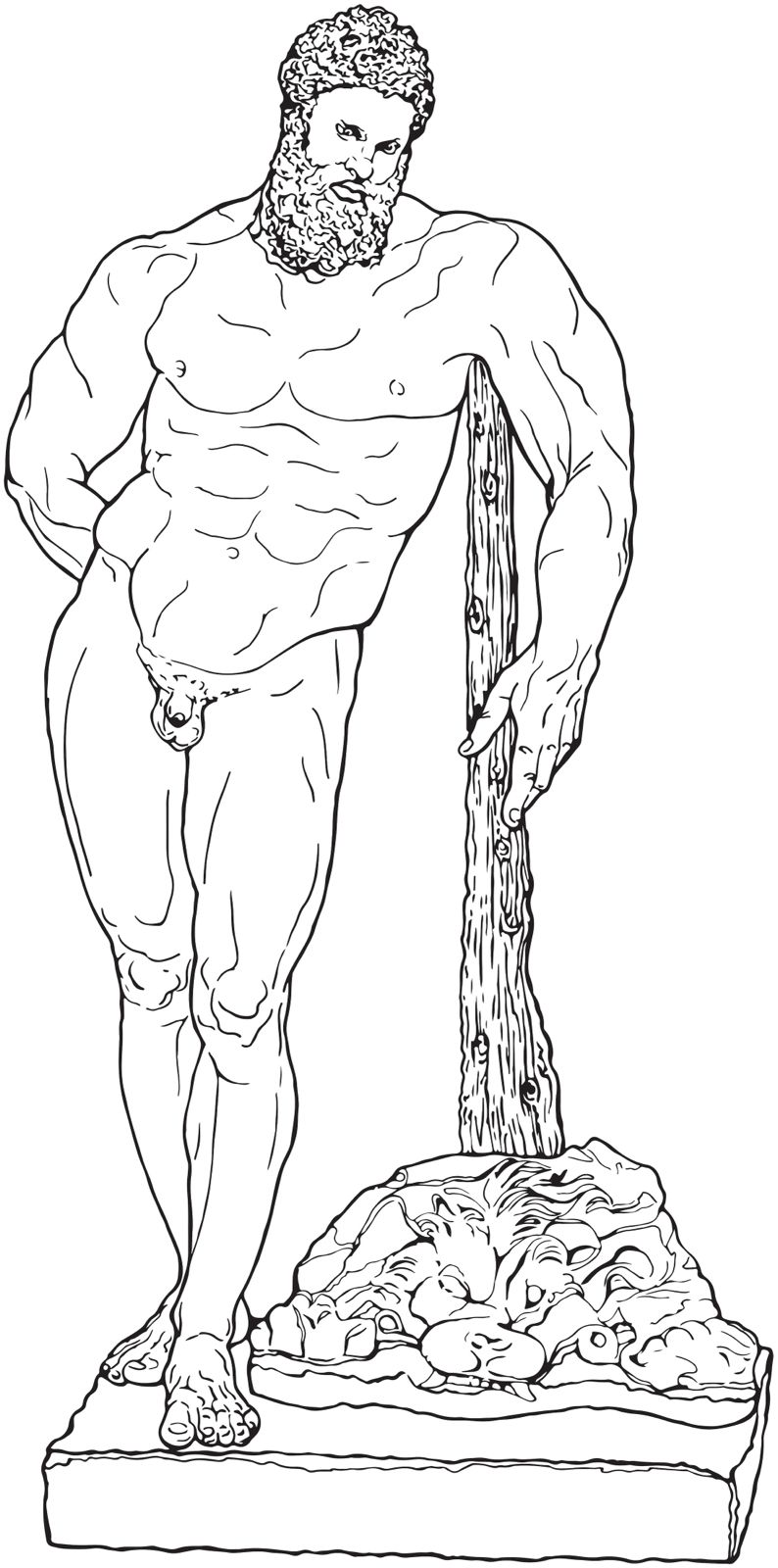

The sculpture depicts the skin of the Nemean lion of Hercules. The beast’s mouth lies flat on the ground with its eyes closed and its fangs embedded into the ground. Only a handful of strands are visible in its mane and on either side of the head are its front legs. The rest of its skin is folded behind onto its back, on which an impression is still visible, made by the feet of the statue of Hercules, who in his great victory sat on the slain wild animal.

The fight against the Nemean lion was the first of the twelve labours carried out by Hercules. The beast was of divine descent, although its exact origin is disputed. According to Hesiod, the lion was the offspring of a two-headed dog named Orthus and a hybrid creature (lion, goat and snake) referred to as the Chimera. The lion was endowed with extraordinary size and strength, and spent its time terrorising the region of Nemea. One evening, Hercules surprised the lion under an olive tree, where it was resting after its meal. At first, he tried to kill it with an arrow, but soon realised that the beast was unaffected by this. He then attempted to stun it with his club, but finally chose to choke it with his bare arms. Once it was dead, he used the lion’s own claws to skin it, on Athena’s advice. The lion’s skin, along with his club, became Hercules’ trademark in Greek iconography. The skin is usually seen tied around his neck like a cape with the head of the lion serving as a helmet.

Notes

The sculpture examined here depicts this famous lion skin. It lies in a heap on the ground, as if the hero had let go of it after accomplishing his work. The monstrous animal’s eyes are closed, showing that it is indeed dead. Its closed mouth reveals its powerful canines and one can also make out the claws of the lion’s front legs. The many folds in its skin merge with the fluent strands of its mane. At the back of the stone block there is a rounded, unpolished cavity. Evidently, it corresponds to the location of the club on which Hercules leaned, using it as a cane. The club, which was made separately, was sealed in this cavity. Therefore, the sculpture belonged to a statue which depicted the hero standing over the lion in a resting position. The lion skin lay on the pedestal, separate from the hero’s legs which occupied the right side.

The sculpture examined here depicts this famous lion skin. It lies in a heap on the ground, as if the hero had let go of it after accomplishing his work. The monstrous animal’s eyes are closed, showing that it is indeed dead. Its closed mouth reveals its powerful canines and one can also make out the claws of the lion’s front legs. The many folds in its skin merge with the fluent strands of its mane. At the back of the stone block there is a rounded, unpolished cavity. Evidently, it corresponds to the location of the club on which Hercules leaned, using it as a cane. The club, which was made separately, was sealed in this cavity. Therefore, the sculpture belonged to a statue which depicted the hero standing over the lion in a resting position. The lion skin lay on the pedestal, separate from the hero’s legs which occupied the right side.

Although the sculpture is an accessory element of the statue, the lion is treated extremely delicately, to such an extent that one could believe it to be an independent work. In terms of the sculpture’s relationship to the viewer, if one imagines the statue on a pedestal of a certain height, the lion skin would have fallen before the eyes of anyone approaching it, hence the attention to detail.

This piece of sculpture is of an extraordinary quality. The folds of the skin, superimposed and wrinkled, seem so supple that they are made of starched fabric. Furthermore, the rendering of the lion’s head is of such striking realism that the sculptor most likely had the opportunity of observing this animal up close, at a circus or menagerie, for example.

The work dates from the Roman era, more specifically the imperial era. However, from the polishing of the marble we can infer that it was produced during the reigns of the Antonines, a period in which the emperor Commodus identified greatly with Hercules. One can see the famous Bust of Commodus as Hercules in the Capitoline Museums in Rome, which depicts him with his bare chest, wearing the lion’s skin and carrying the club over his shoulder.

As mentioned above, this fragment of statue, so powerful in its subject and masterful in its execution, is like a work in its own right. In this sense, we may think of the great Rodin, who had a brilliant talent for these kinds of sculptures, which rendered fragments as totally independent from their wholes, giving free rein to the imagination.

Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886-1965)

Giorgio Sangiorgi (1886-1965)

Giorgio Sangiorgi, born in Messina in 1886, was a renowned antique art collector and dealer. As a collector, Sangiorgi accumulated an important collection of antique glasses which he published in 1914. His gallery, located at the Palazzo Borghese in Rome, enjoyed an international reputation and was particularly renowned for its having organised several important auctions. Many masterpieces of classical antiquity from the Galleria Sangiorgi are now kept in private collections as well as being on display at international museums and institutions such as the Corning Glass Museum or the Toledo Art Museum.