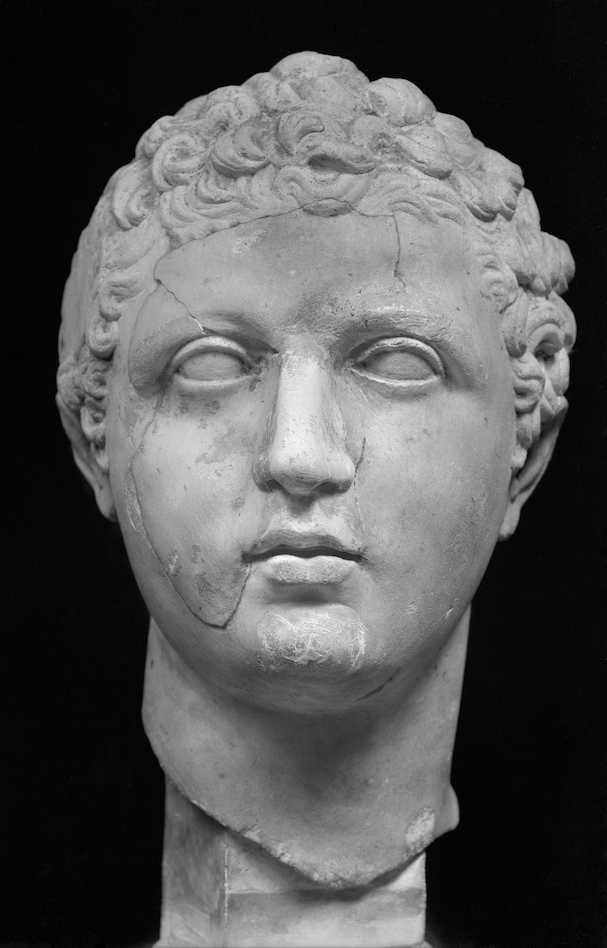

The striking, just under life-sized, clean-shaven head of a young man, with idealised features, is turned slightly to the left. His head is crowned with closely curled luxurious hair, he has a slightly parted mouth with full lips and dimpled corners, with a rounded cleft chin below and perfect straight nose above. The facial features are finely sculpted, with a hint of musculature, cheek bone, and delicate neck folds. The naturalistically modelled head encapsulates both power, innocence and boldness, displaying the skill and virtuosity of the unknown sculptor to incredible effect. Indeed the workmanship can be likened to the great Greek sculptor, Lysippus, whose many bronze masterpieces exhibited the same finesse and dexterity; characteristics often admired and emulated by others. The identification as an athlete can be made by the distinctive facial features of the youth, including the closely cropped hair, challenging gaze and thick muscular neck. Parallels with other known pieces include; the head of an athlete, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Palestrina, Inv. no 568 (cf. illustration), as well as reflecting such iconic works as the bronze Antikythera Youth, National Museum Athens, Inv. no 13396.

The striking, just under life-sized, clean-shaven head of a young man, with idealised features, is turned slightly to the left. His head is crowned with closely curled luxurious hair, he has a slightly parted mouth with full lips and dimpled corners, with a rounded cleft chin below and perfect straight nose above. The facial features are finely sculpted, with a hint of musculature, cheek bone, and delicate neck folds. The naturalistically modelled head encapsulates both power, innocence and boldness, displaying the skill and virtuosity of the unknown sculptor to incredible effect. Indeed the workmanship can be likened to the great Greek sculptor, Lysippus, whose many bronze masterpieces exhibited the same finesse and dexterity; characteristics often admired and emulated by others. The identification as an athlete can be made by the distinctive facial features of the youth, including the closely cropped hair, challenging gaze and thick muscular neck. Parallels with other known pieces include; the head of an athlete, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Palestrina, Inv. no 568 (cf. illustration), as well as reflecting such iconic works as the bronze Antikythera Youth, National Museum Athens, Inv. no 13396.

Pentelic marble

Pentelic marble is from a quarry complex on the slopes of Mount Pentelicus, some 16 km. north of Athens. The stone is characterised by its fine grain and pure colour; the white tinged with a golden hue. In Classical times the south slopes were pockmarked with over 25 quarries, much of the stone was destined to be used for the buildings and sculptures of Athens especially during the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. From the 2nd century B.C. onwards, with the rise of the Roman empire, large quantities of stone was shipped to produce statuary, sarcophagi as well as architectural detailing.

Gavin Hamilton and the Lansdowne Collection

Gavin Hamilton, originally born in Lanarkshire, Scotland, will be forever linked with the 18th  century Grand Tour. Having studied at the University of Glasgow, Hamilton, became an accomplished painter, using the classical world as his inspiration. He travelled extensively in Italy, eventually settling in Rome. He was there not only to paint but to undertake excavations, specifically, between 1769-1771, of Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. Hamilton often spending days in the swampy low-lying area, known as the Pantanello, adjacent to the site. Much of the statuary from the villa complex was deposited there, by unknown hands, as the instability of the later Roman empire unfolded, there they lay, forgotten and undiscovered, for some 1200 years. Hamilton quickly realised that there was a huge thirst for antiquities, with prominent members of British society looking to establish their own collections following their visits to the great ancient sites as part of their Grand Tour. Soon Hamilton was one of the most highly regarded purveyors of Roman sculpture, renown for both his integrity and aesthetic judgement. His extensive journals and correspondence provide an incredible record of the formation of many of the United Kingdom’s key private and public collections.

century Grand Tour. Having studied at the University of Glasgow, Hamilton, became an accomplished painter, using the classical world as his inspiration. He travelled extensively in Italy, eventually settling in Rome. He was there not only to paint but to undertake excavations, specifically, between 1769-1771, of Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. Hamilton often spending days in the swampy low-lying area, known as the Pantanello, adjacent to the site. Much of the statuary from the villa complex was deposited there, by unknown hands, as the instability of the later Roman empire unfolded, there they lay, forgotten and undiscovered, for some 1200 years. Hamilton quickly realised that there was a huge thirst for antiquities, with prominent members of British society looking to establish their own collections following their visits to the great ancient sites as part of their Grand Tour. Soon Hamilton was one of the most highly regarded purveyors of Roman sculpture, renown for both his integrity and aesthetic judgement. His extensive journals and correspondence provide an incredible record of the formation of many of the United Kingdom’s key private and public collections.

William Petty-FitzMaurice, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, was an Irish born British politician, who after attending the University of Oxford, rose through the Whig political ranks to become firstly Home Secretary and finally Prime Minister. In 1763 the Marquess acquired, from John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, a majestic Robert Adam’s designed house in the heart of fashionable Mayfair, the house, at the south side of Berkeley Square (cf. illustration), was still under construction, and would be soon named Lansdowne House. After visiting Italy in 1771, he resolved to adorn his new London home with a collection of ancient sculpture, which was eventually to become one of the leading collections in the country. He turned to Gavin Hamilton to source and advise him on purchases to be housed in the specially designed galleried space.

William Petty-FitzMaurice, 2nd Earl of Shelburne, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, was an Irish born British politician, who after attending the University of Oxford, rose through the Whig political ranks to become firstly Home Secretary and finally Prime Minister. In 1763 the Marquess acquired, from John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, a majestic Robert Adam’s designed house in the heart of fashionable Mayfair, the house, at the south side of Berkeley Square (cf. illustration), was still under construction, and would be soon named Lansdowne House. After visiting Italy in 1771, he resolved to adorn his new London home with a collection of ancient sculpture, which was eventually to become one of the leading collections in the country. He turned to Gavin Hamilton to source and advise him on purchases to be housed in the specially designed galleried space.

Eventually the Lansdowne Collection would include, along with this mesmerising head of an Athlete, over 100 superb sculptures, exemplary examples of their type, indeed many are now to be found in leading museums around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum, the Getty Museum and the Louvre.

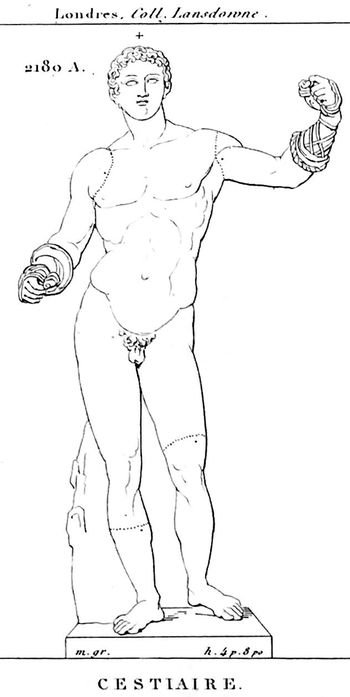

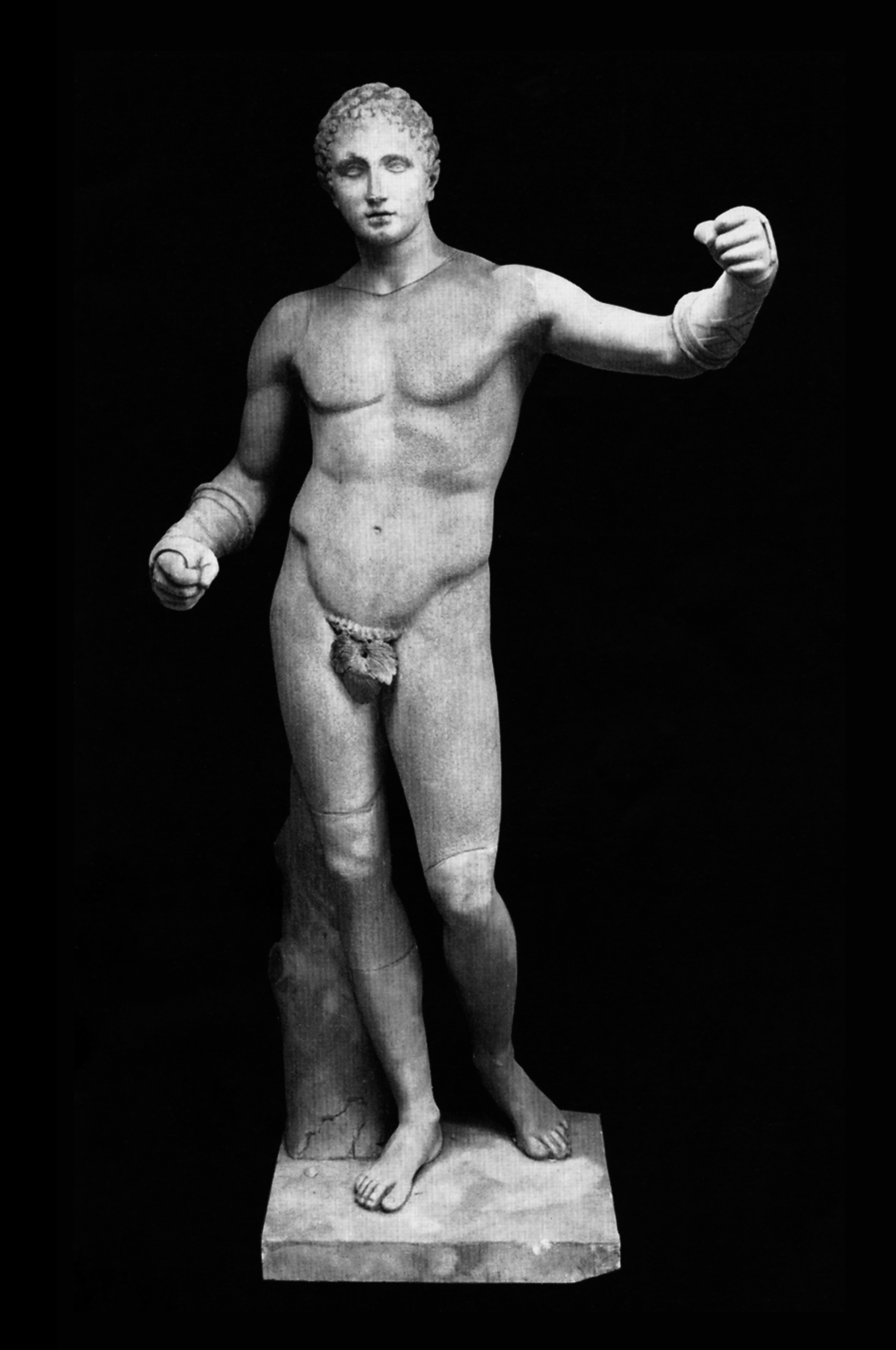

Before joining the Lansdowne collection, as was common practice at the time, the head passed through the Rome workshop of the renowned sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (1716-1799). Cavaceppi erroneously married the head to a torso of the diadoumenos, a youth tying a fillet around his head. Additionally, arms, lower legs and a base were added, thus the head in its newly acquired form was given the name of ‘Cestiario’ or Boxer, and illustrated as such by Charles Othon de Clarac in 1851 (cf. illustrations). This restoration reflected the popularity of combat sport in 18th-century England. Cavaceppi's reinterpretation of the sculpture demonstrates how commercial interests and collecting tastes took precedent over academic considerations. It was only after the 1966 Sotheby’s sale that the head was subsequently removed from the incompatible torso, to once become as found by Gavin Hamilton and as we see today.

This head, with its mismatched torso and base, was included in a shipment of antiquities sent to Petty-FitzMaurice and mentioned in correspondence by Hamilton. On 6 May 1775, he writes about the shipment, stating; ‘I have sent your Lordship inclosed (sic) a note of the statues I have shipped off for your garden, which I may venture to say are the best that ever were put in any garden in England.

The Marquess of Lansdowne was evidently delighted with this new addition to his burgeoning collection and the Cestiario was positioned, not in the garden as first suggested by Hamilton, but in the entrance hall, standing in the right-hand of a pair of apses which flanked the doorway that lead to the main staircase. The piece remained an integral and prized part of the Lansdowne Collection, welcoming distinguished visitors to the house, for over 150 years.

After the sale of the statue at Christie’s in 1930, where much of the London collection was dispersed following the economic upheaval of the previous decade, the athlete found its way into the Lorbet-Altounian Gallery, Mâcon, before arriving back in London where it was listed in a warehouse inventory of 1953. In 1966 the statue was once again at public auction, with Sotheby’s selling it to Rudolph Forrer, numismatic expert at Spink and Sons, presumably bidding on behalf of a private client.

The head has featured in numerous publications over the years including the revered record by Michaelis, Ancient Marbles in Great Britain (1882), and most recently in Angelicoussis’, Reconstructing the Lansdowne Collection of Classical Marbles (2017), although unfortunately the author was unable to examine the head in the flesh.